Understanding Balance sheet — The one without jargons

Meet Luca Pacioli — he’s the one who isn’t staring at you

Luca, a monk by trade, was your regular Renaissance poster boy who did cool things, including teaching math to Leonardo da Vinci

He is credited with popularising the method of double entry of bookkeeping* back in the 1400s, and is incidentally also known as Father of Modern Accounting

*Though double entry bookkeeping existed since the 11th century, it was made “mainstream” by Luca, who talks about it extensively in his book — Summa

Method of double entry of bookkeeping is just another way of saying

The very day credit is born, it has a twin called debit. You can’t think of credit in isolation — where there is credit, there is debit

Much like the Twin towers of Deutsche Bank@Frankfurt, playfully called Credit and Debit — You do not take the name of one without the other

This inseparability of Credit and Debit is one of the most important concepts that allowed trade practices to accelerate in the 15th century — The method allowed banks to deal with complex transactions involving multiple accounts all over Europe

Pay close attention now, for I am about to tell you another story with you as its central character!

As a proud owner of a new record store, you can’t stop telling all your friends how you put in your own $100 to start the business

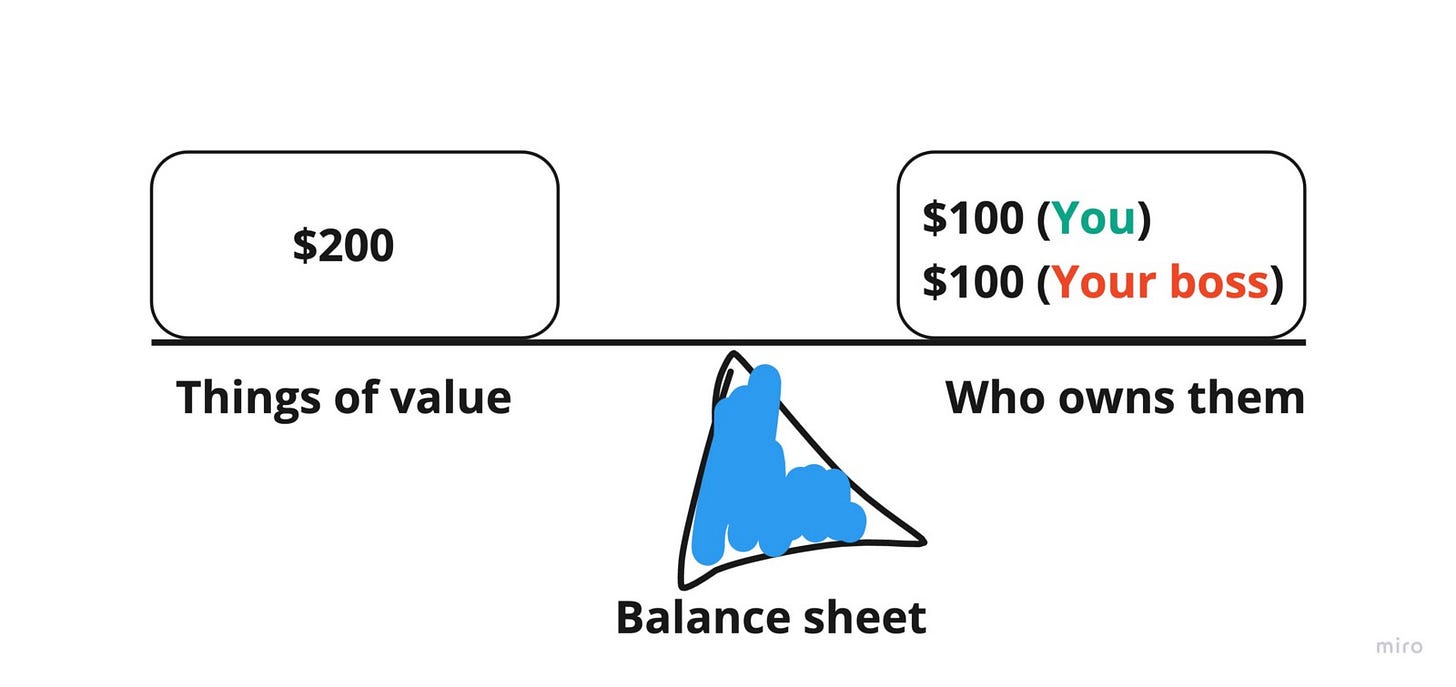

In-fact, you love the story so much, you had this flyer printed the very day you started the business, and framed it on your plastered yet resolute office walls

In addition to capturing your pride well, the flyer also captures the status of your ownership, that is — You funded your business with $100 cash, and you own a 100% of it. Put differently, you own 100% equity of the business, and in turn, everything of value that your business owns

Imagine that flyer in your hands now, it’s a light sheet of paper that has both sides well balanced — That right there, dear reader, is also your company’s Balance sheet

A balance sheet is a statement that captures ownership of things that are of value

As you will soon find out, a Balance sheet gets outdated the moment it is created, as it is always prepared with respect to a single point in time, thus taking specific dates — For eg, end of a quarter(31st March) or year(31st Dec)

Just like this story, over time, your business starts gathering momentum. But along the way, you realise you need more money to run your day to day operations — You very well realise that hustle works well with opening of doors, not so much with paying for bills

Not the one to give up easily, you reach out to your old boss, who agrees to lend you $100 worth credit, because he finds you creditworthy

Remember the twins from before? — No one says the name of one without the other — The moment you avail credit of $100, you bring alive a debt of $100. And who is liable to pay that debt? You.

But for now, you are grateful for the credit

You wake up next day with a smile on your face. You stretch out, discovering lighter shoulders and heavier wallet

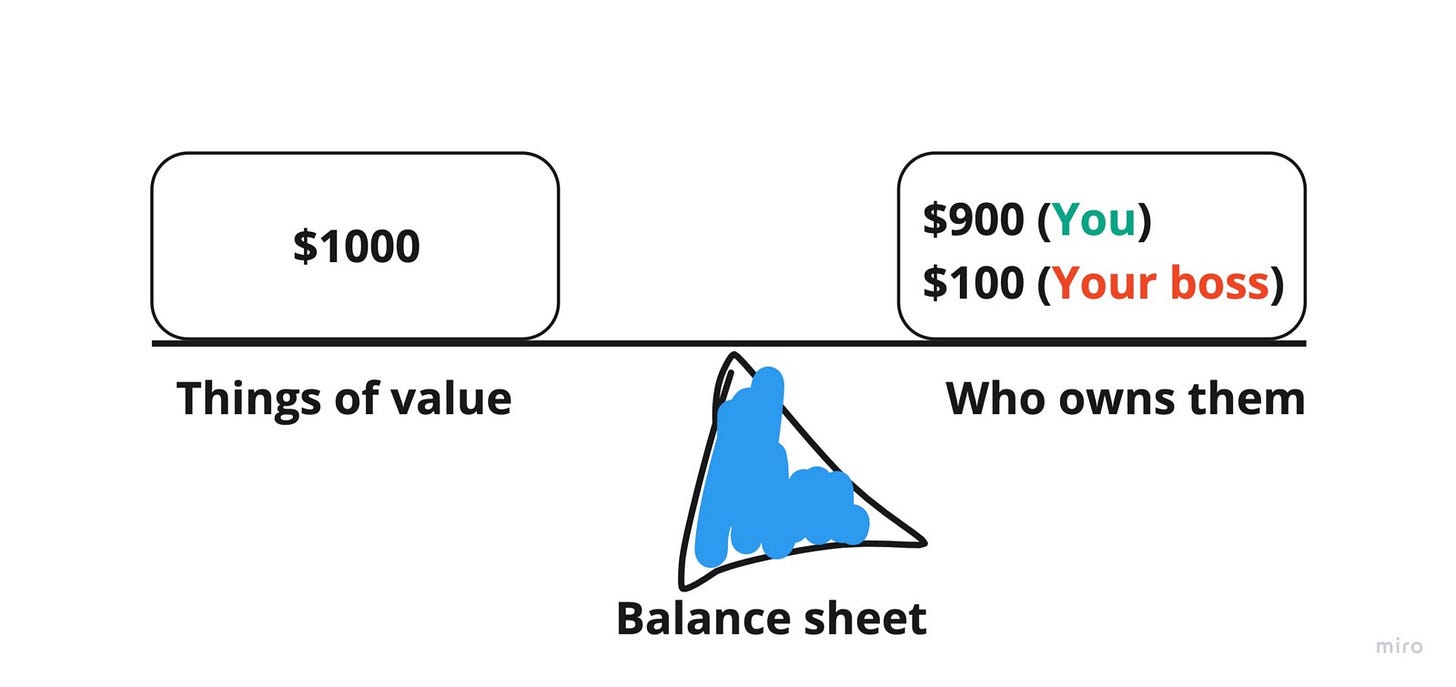

With the recently acquired debt, you decide to revisit your Balance sheet. Remember, Balance sheet is outdated the moment it is prepared

You know that while your business is now in possession of cash worth $200, you only own $100 — your original investment. Your boss can stake claim to the other $100 (plus interest) by virtue of the credit he extended, which until its paid back, is a liability you own

“Why would you take on debt if your eventual goal is to retain maximum ownership of your business” — Every time your hear your family ask this, you shake your head while repeating the same set of words — Because sometimes taking debt is a great way to grow your business

You also remind your family that your old boss isn’t looking for ownership of the business; he’s just expecting his credit paid back with interest and maybe some gratitude — All within an agreed upon timeframe

Your family breathes easy when they realise that the moment your boss gets back what you owe him, any future claims of ownership would be legally void

However, until then, you know your ownership of the business has gotten lesser, while your ownership of the debt is at 100%

Being sharp, you also realise that even though your ownership is reduced, the business still has more cash to spend, irrespective of who funded it.

Fast forward few months, things are going smooth, well at-least for your competitors. For you, the business has not been able to cut costs and grow revenue

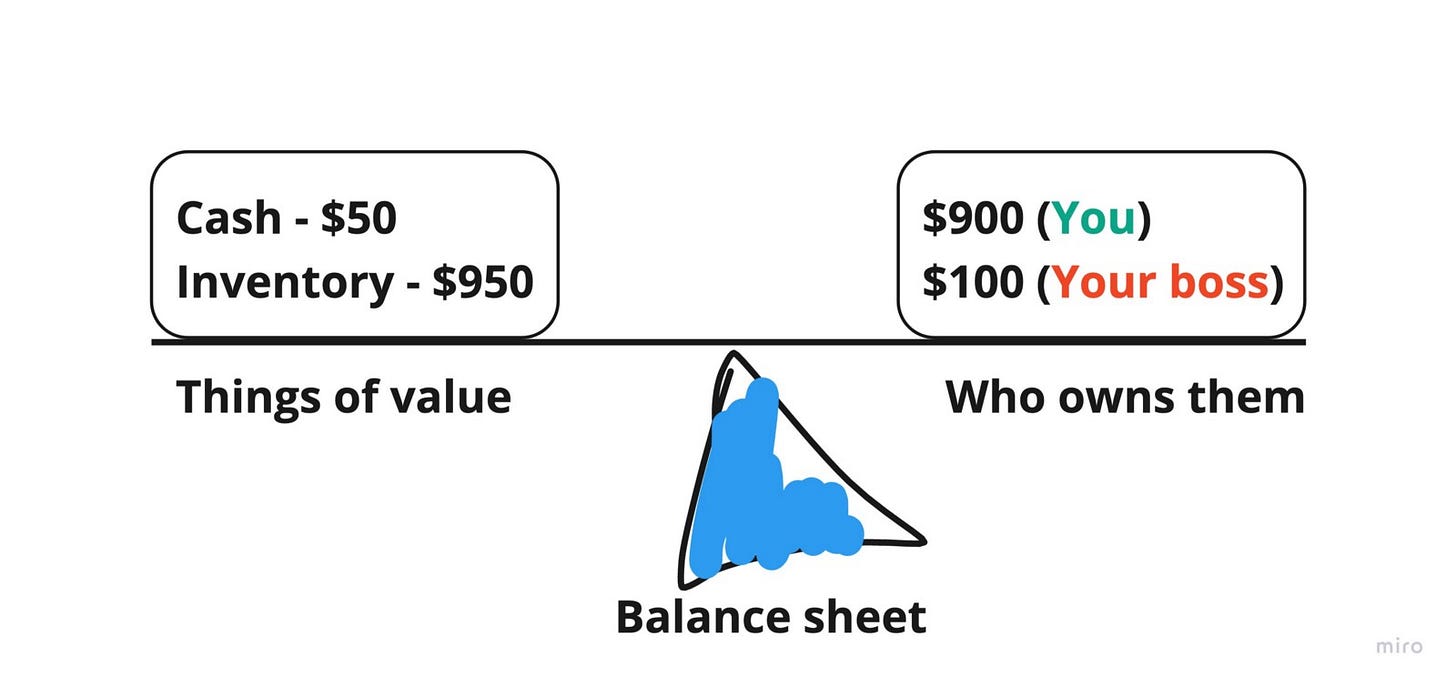

Feeling rushed by the approaching payback time, you choose a befitting gloomy day to look at your balance sheet again, trying to assess the current state of your business

Ok… so you know your business has $1000 at its disposal. But you also know that it’s not all cash. You hold inventory (music records) which hold tangible value, but isn’t cash

You rummage through the entire store and figure out you have about $950 worth of records that haven’t sold

The day gets gloomier the moment it sinks in that you have only $50 of cash, but you need more than $100 to pay back the debt

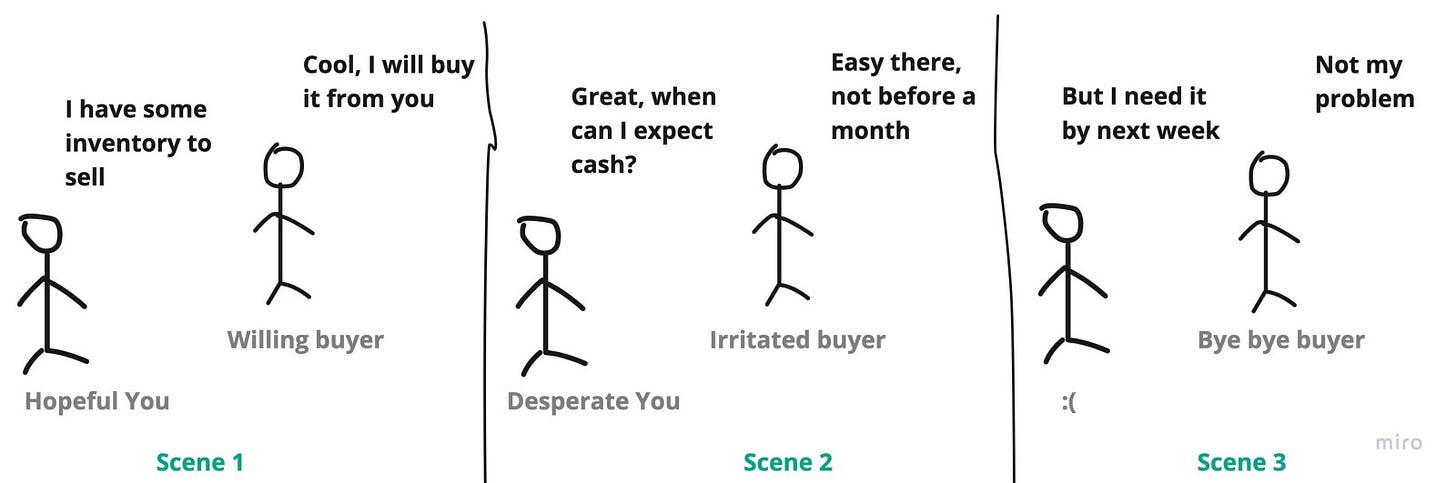

You look around your empty office, as if asking for any available opinions. Finding none, you take few deep breaths and decide to sell some of your inventory for cash, so that you can pay your boss within the agreed upon timeframe

You go out and chase prospective buyers who might buy your inventory in bulk. Need I remind you how those conversations went(sideways)…

Weary with anxiety, you go back to your boss, asking him if he would be willing to barter some of your inventory in lieu of the cash you owe him — The only good that comes out of that conversation is the old guy gets an unexpected cardio session

Feeling aimless, much like the pebbles you kick on your way back, you are at-least kept company by two important realisations

Creditors expect be paid back in Cash

Not everything of value can be immediately converted to cash

With the two takeaways by your side, you keep whispering to remind yourself

Nothing converts to cash like cash; Nothing converts to cash faster than cash

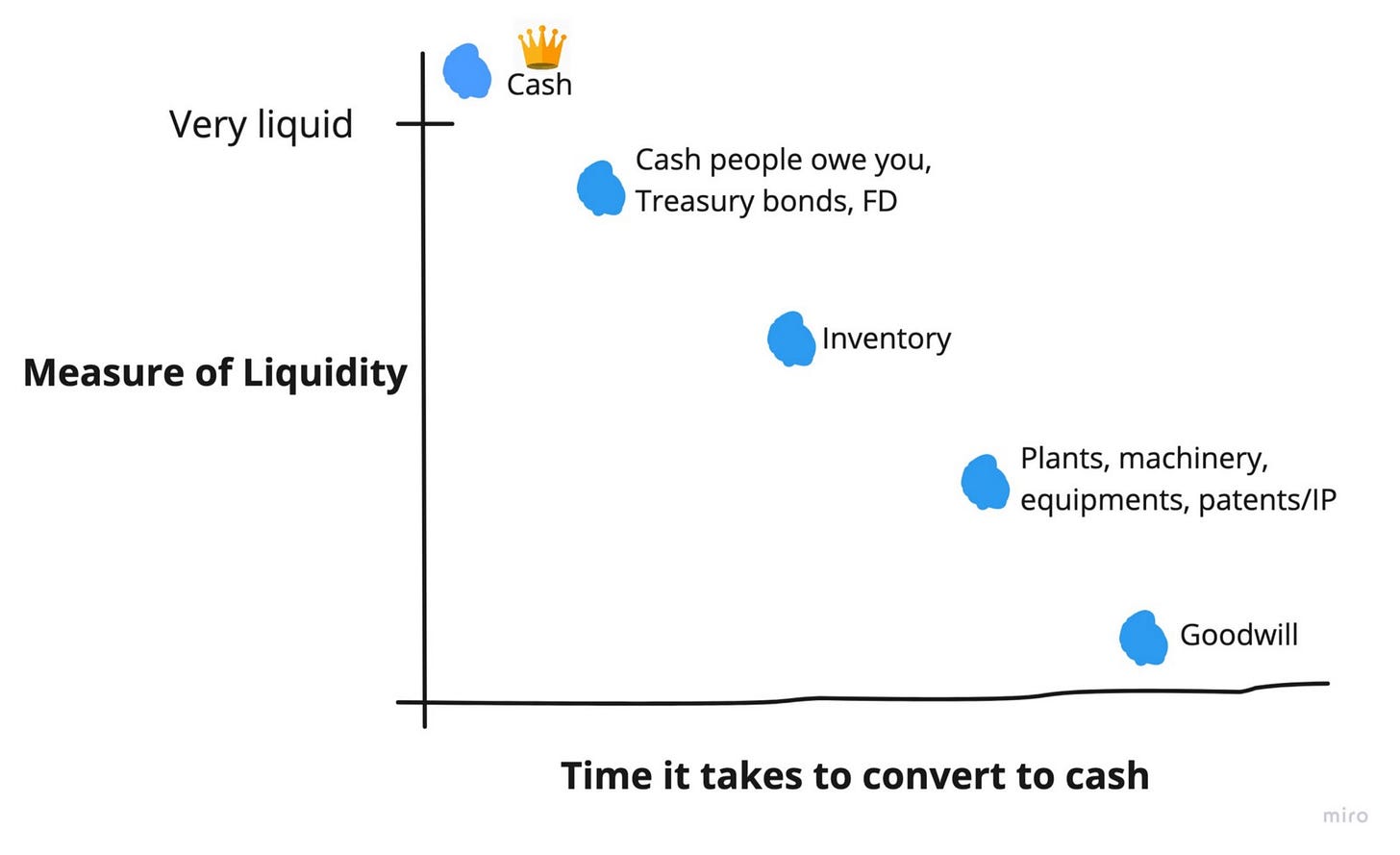

The important realisation you had on your way back, the world has a name for it — Liquidity

The easier it is to convert something of value to cash, the more liquid it is

This new found perspective extends fluidity to your thoughts too — You realise that you have to view things owned by the business using the “liquidity tinted” glasses — For it provides the real picture of what you think is valuable v/s how soon can you unlock and avail that value

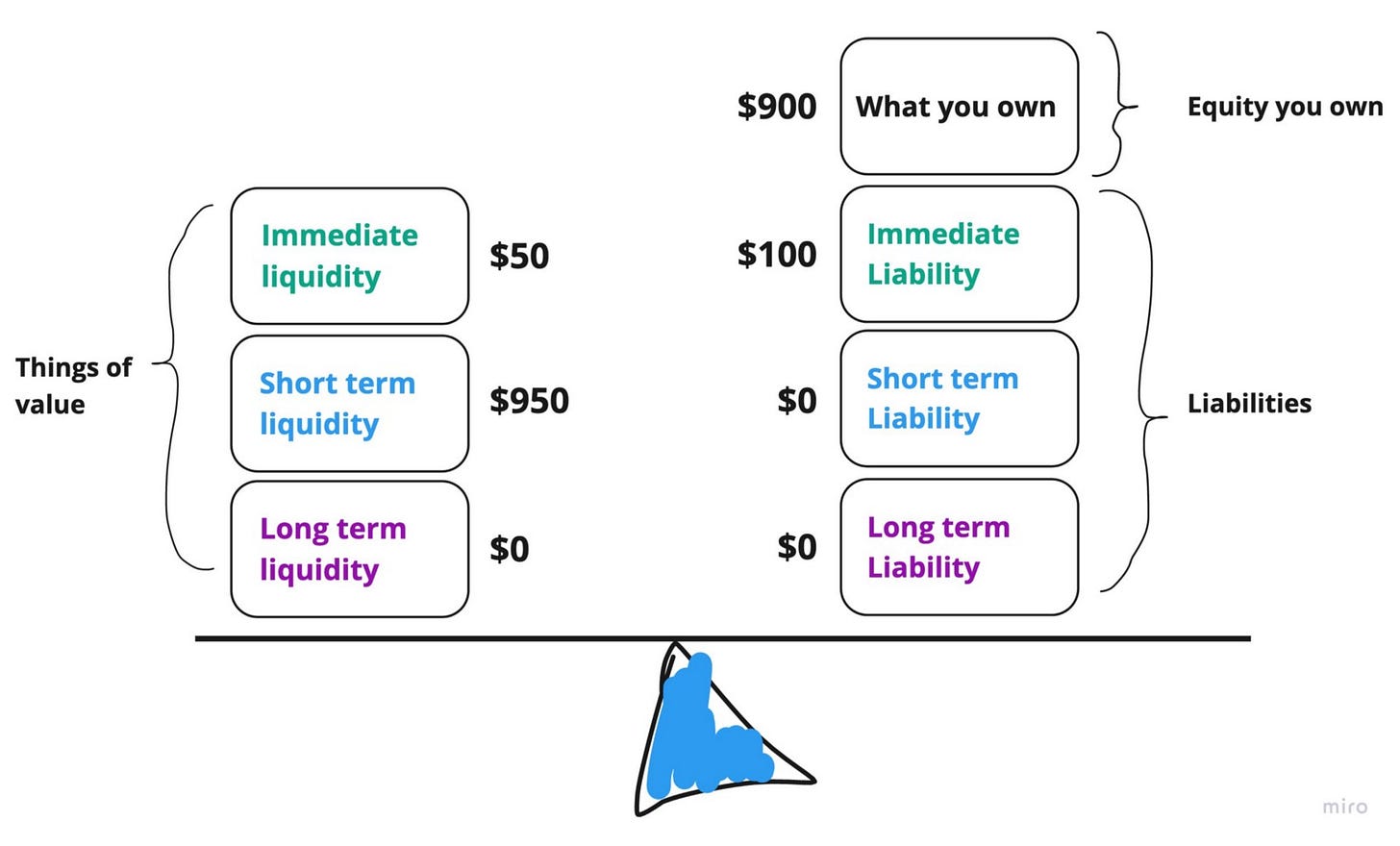

With new found respect for liquidity, you start looking at your Balance sheet from the perspective of “how soon do I have to pay liabilities” and “how much liquidity does my business have at its disposal”

What you do next is real smart. You sort everything of value that the business owns in decreasing order of liquidity. You do the same for liabilities, only in decreasing order of urgency

As incredulous as Columbus must have been when he saw the American shores for the first time, you too clearly see for the first time that while your Balance sheet was apparently balanced with $1000 on both sides, the moment you factored in liquidity concerns, the balance was out of whack — Your immediate liability was $100, but your immediate liquidity only $50

You are also greeted with a discomforting realisation that maybe there are more nuances up for grabs, hiding in plain sight. You get to work

But before that, you decide to formalise the concepts you learnt by switching to the “industry parlance”, so that people who are reading this story can generalise and identify these concepts outside of your story

You know that an asset is any thing of value that your business owns

You also realise that the standard way to rank assets on the liquidity axis is by using the terms “Current” and “Non-current” — The former means these assets have liquidity of ~12 months, the latter has liquidity of >12 months

Remember, liquidity is the time it takes for an asset to convert to cash. The easier it is to convert to cash, the more liquid that asset is

The same grouping works well for liabilities — Current and Non-current liabilities — Debt or financial obligations that you have to pay in ~12 months or >12 months respectively

With this slightly more formal representation of Balance sheet, you start thinking of signals you would want to capture to measure the vital stats of the business, and thus avoid being thrown off-balance as you just were

1—How much liquidity does my business have for all Current liabilities?

You have $1000/$100 = 10, which means, for every dollar of your current liability, you have $10 of liquid assets

This is called the Current Ratio

Can you imagine the above scale tipped towards the other side?

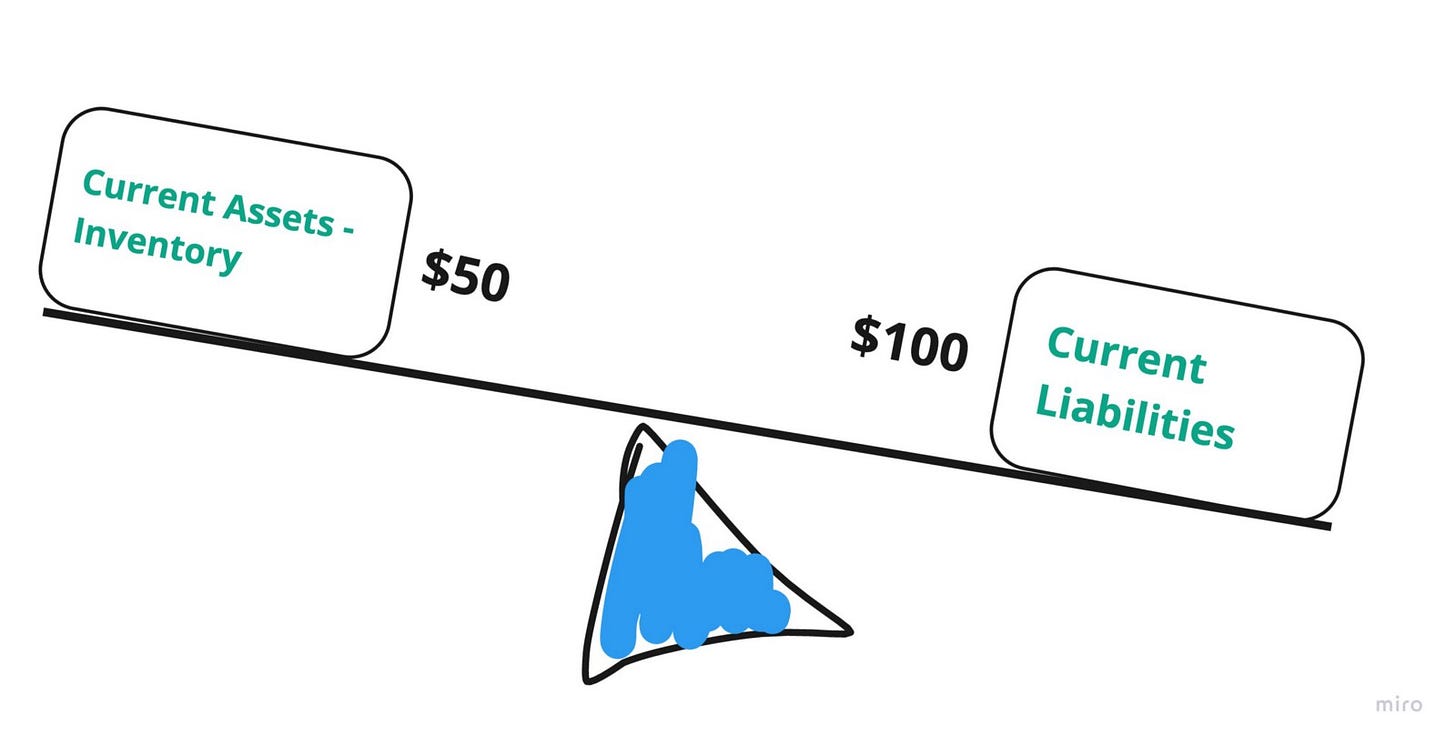

2—How much liquidity does my business have in case I had to pay all my current liabilities tomorrow?

As you can see, the only difference b/w this ratio and the Current ratio is that we subtract inventories from the current assets*, you of all know why — Because inventory is not as liquid as we think

You have $50/$100 = 0.5 times liquidity if you had to pay off all your Current liability tomorrow. Which means, for every dollar of immediate liability, you had only $0.5 of liquidity

This is also called the Quick Ratio. There’s another word for it, “Acid test”. You know more than anyone how apt a name that is, don’t you

*If you go back to the liquidity chart, you would have noticed that between Cash and Inventory, you have something called Cash equivalents (Mostly government issues bonds) which are more liquid than inventories but less liquid than cash. These are always included as part of Current assets while calculating Quick Ratio. Other lines items that are included are Account Receivables

3—How much liquidity does my company have exclusively in cash?

You have $50/$100 = 0.5 times liquidity explicitly in cash. Which means, for every dollar of current liability, you had only $0.5 of cash in hand

This is also called the CashRatio. It comes in handy when you want to judge companies based solely on their cash availability

4—How much of the business is not owned by me, but by creditors?

You have $100/$900 = 0.11, which means, for every dollar of equity, there’s a debt of $0.11 to be paid. This is also called the Debt:Equity Ratio. As a business owner, would you prefer a higher or a lower Debt:Equity Ratio?

5—How much of debt is there on the business?

You have $100/$1000 = 0.1, which means, for every dollar of asset, there’s a debt of $0.1 to be paid. This is also called the Debt Ratio

With the nascent intuition to extract insights from a Balance sheet, you decide to put your understanding to test

You knew that, as a business, your humble record store had not exposed you to enough complex cycles of asset and debt management, so you decide to look at the Balance sheet of one of your favourite business — Netflix

Your immediate observations are

This balance sheet is as of 30th June 2020. That means from then till now, Netflix might have picked up more debt but that won’t be reflected till they prepare the next Balance sheet. How convenient for companies to raise debt after a Balance sheet is prepared!

Aligned with your observations, you see that even Netflix ranks assets in the decreasing order of liquidity, and ranks liabilities in order of urgency. Even Netflix understands the power of liquidity

You see some familiar terms, like Retained earnings — You had seen this when you were making your Income Statement… It makes sense to you now. Any net earnings is obviously a liquid asset that the business owns, and the right to ownership of that lies with the equity holders!

With some swift strokes on the calculator, you realise that the Current ratio of Netflix is—

Current assets/Current liabilities = $8,564,139/$7,626,418 ~1.1

So, as of 30th June, Netflix had $1.1 for every dollar of current liability. Now, obviously that number doesn’t make a lot of sense without knowing the benchmark for the particular industry in which Netflix operates

The remaining ratios haven’t been calculated as it is trivial to do so — There are excellent resources to verify, for eg, here and here

Anyone who read this far, will find me in their debt. I hope this article was able to convey the origins of why a Balance sheet does what it does. I plan to follow this up with two more pieces—Income & Cash Flow statements, thus bringing all the key financial statements together and understand their interplay (I hope you read them too)

If you found your story as a young business owner well articulated, consider sharing it with your friends!

Liminal indicates a state of transition. This blog is simply a result of the notes I take when I try to learn new and interesting concepts. I try to do so in a way that includes visuals and less jargons (I hate them)

If you subscribe, you can expect not more than one article every fortnight- Some of the future topics range from Confusion Matrix, Calculus for the forgotten, P&L statement, and my personal favourite—Leaves:Why are they shaped the way they are